This was a piece written by Professor Emeritus of Political and Medical History at the University of the West Indies (U.W.I.), Professor Pedro L.V. Welch, in defense against claims that Christianity was a promoter of slavery. Professor Welch was a former Deputy Principal and former Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Education at the U.W.I. Cave Hill campus, Barbados.

I write in response to a recent article by a prominent Barbadian entrepreneur on the role of Christianity in furthering the oppression, particularly, of people of African descent.

The core of the charge is that Christianity is part of an amalgam of social, political and colonial structures that underlie the continued denial to Blacks of their expectations of self-actualization. I wish to apply an historical approach in seeking to counter such a charge as it related to Caribbean slave societies.

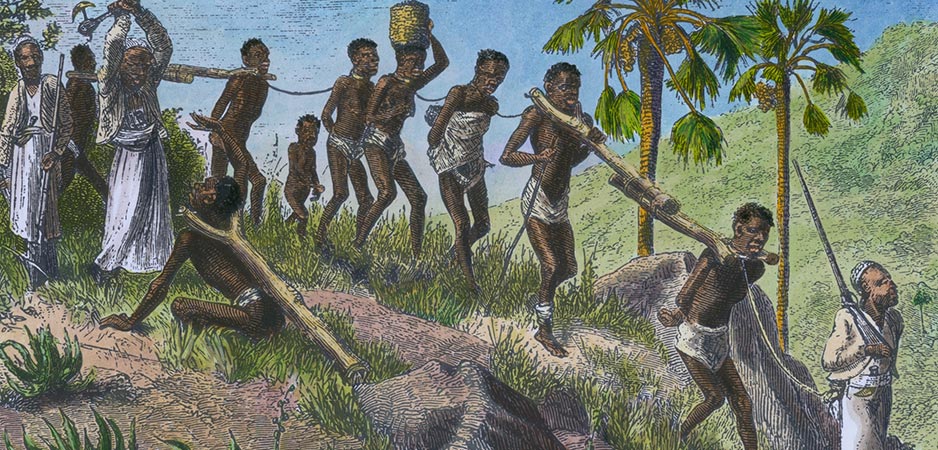

When Europeans reached the Caribbean, Christianity had not long been entrenched in European society. Slavery had existed in Europe long before the movement to the New World. However, when the English arrived, there were no laws governing the institution of enslavement. Over time, in the English New World colonies, with Barbados as the template, colonisers codified the various statutes that would govern their property in human beings.

From the passing of the first slave law in Barbados in the 1660’s, one central theme in the minds of the framers was that Africans were distinguished from Europeans on the basis of race and “barbarism”. Indeed, we may note that as far as the planters were concerned, Africans were unfit to be governed by the laws that governed Whites. Such views corresponded to a general reluctance to proselytise among the enslaved.

Moreover, planters generally understood that to Christianise an enslaved man or woman posed a threat to their maintenance of what they perceived to be the desired social order.

This was not confined to the Caribbean. In the United States, as Frederick Douglas, a formerly enslaved man, informs us, planters were generally opposed to enslaved people reading the Bible or, for that matter, acquiring literacy. The point here is that far from introducing Christianity to control the enslaved, most enslavers were clearly of the view it was in their interest to keep their enslaved workers as far from the Church as possible.

How did Christianity come to have such a powerful influence among Blacks, both in the pre- and post-Emancipation periods throughout the Western Hemisphere? If we avoid the general arrogance and lack of respect which some critics exhibit towards our enslaved ancestors, we might at least develop some understanding of the relative truth. The truth is that the enslaved most clearly had the capacity to analyse the hypocrisy of the enslavers, and it is more accurate to say they adopted Christianity in spite of, rather than because of, brainwashing by the enslavers.

Take, for example, the case of Equiano. He had adopted the Christian faith but this in no way prevented him from being critical of the system of enslavement practised in the West Indies. We even find him penning a letter to the monarch of England “on behalf of my African brethren”, charging the Jamaican Assembly with crimes against the enslaved in a recently passed slave law (1787).

Equiano was by no means the only formerly enslaved to adopt Christianity and, following conversion, to maintain an independent stance against the prevailing social system.

The formerly enslaved fighter, Tula, who led a rebellion in Curacao in 1795, expressed avowedly Christian sentiments when in a dialogue with a Catholic priest. He reportedly said: “Father, do not all the persons spring from Adam and Eve? Was I wrong in liberating 22 of my brothers who were unjustly imprisoned?…When I was liberated, I fell on my knees and cried to God….”.

In Tula’s thinking, the theology of the Bible vindicated his freedom efforts. The same is true of Daddy Sharpe and the enslaved men and women who fought in the biggest rebellion to be launched by the enslaved in Jamaica. This took place in 1831-1832 and is often called “the Baptist War” or “the Christmas Rebellion“.

The fact is the leaders of that rebellion were converts to Christianity who had found in the Hebrew Scriptures the themes of freedom that resonated with their ideas of resistance. It should not surprise us that stories of the Exodus and other narratives might offer parallels with their own struggle.

We may also note that in Jamaica and elsewhere in the Caribbean, while some enslaved began to attend Church of England services, many became members of the non-conformist churches that to them reflected a closer approximation to their expectations of Christian witness.

In particular, Blacks saw the Baptists as representing their interests. One Baptist missionary, a white Englishman, wrote in the 1830’s that the black population saw the missionaries as being independent of the planters and that “they were almost the only individuals on the island who dared to interfere between the oppressors and the oppressed”.

Additionally, in Jamaica, as in some parts of the American south, the enslaved and the formerly enslaved formed their own churches led by Blacks. Thus, we note the rapid growth in Jamaica of the so-styled “Black Baptists” led by Thomas Leisle and Moses Baker.

On one occassion, a white Baptist minister, William Knibb, beloved by the masses, was reported to have been shot by planters. In that case, as Robert Stewart in his book “Religion and Society in Post-Emancipation Jamaica” tells us, the Baptist masses “were in a mood to eliminate all Whites and Mulattoes”. Even well after Emancipation, the leaders of the Morant Bay Rebellion of 1865 in Jamaica were largely drawn from the Baptist churhes.

The historical evidence does reveal that in order to justify the enslavement of Africans, some Europeans employed several myths, including one based on the allegation that Africans, as descendants of the Biblical Ham, were under a curse that condemned them to be slaves to others. However, even the most cursory reading of the Hebrew text would show that no curse was ever proclaimed on Ham.

Moreover, such distortions of the Biblical narrative should not be employed to argue that Christianity supported the oppression of our ancestors. Indeed, in Britain, it was the reawakening of primitive Christianity that provided the moral basis for anti-slavery sentiments to emerge and grow in the 18th and 19th centuries. True, other factors, some economic, were employed, but that does not deny the influence of Christian teaching.

If we extend our discussion to the situation in Barbados and elsewhere in the Anglophone Caribbean up to the 1930’s, we do well to take note that many radical thinkers had strong Christian leanings. We can detect such connections in the Marcus Garvey U.N.I.A., against which we would hardly launch a charge of being brainwashed.

It is impossible for me in this forum to produce the voluminous evidence that exists to support my contention that Blacks were quite capable of accepting the teachings of the Bible, and of formulating an independent theology of resistance. Of course, I say to critics of the Christian faith that you are free to contest my argument but you are not free to manufacture your own evidence.

Indeed, I would suggest that it might be a good thing to abandon any feelings of arrogance and contempt in challenging the right of our formerly enslaved ancestors to adopt a faith they saw that offered them dignity and meaning.

Some critics may not see it that way, but their disagreement does not make them right and our ancestors wrong.

I recommend my two articles in Historical Papers, Published by The Canadian : Society of Church History: The Role of the Bible in the British Abolition of Slavery, 2000 and Emancipation Theology and the British West Indian Plantocracy, 2001.

Thomas A. Welch